NASA’s Cleanest Rooms Are Evolving New Forms of Bacterial Life

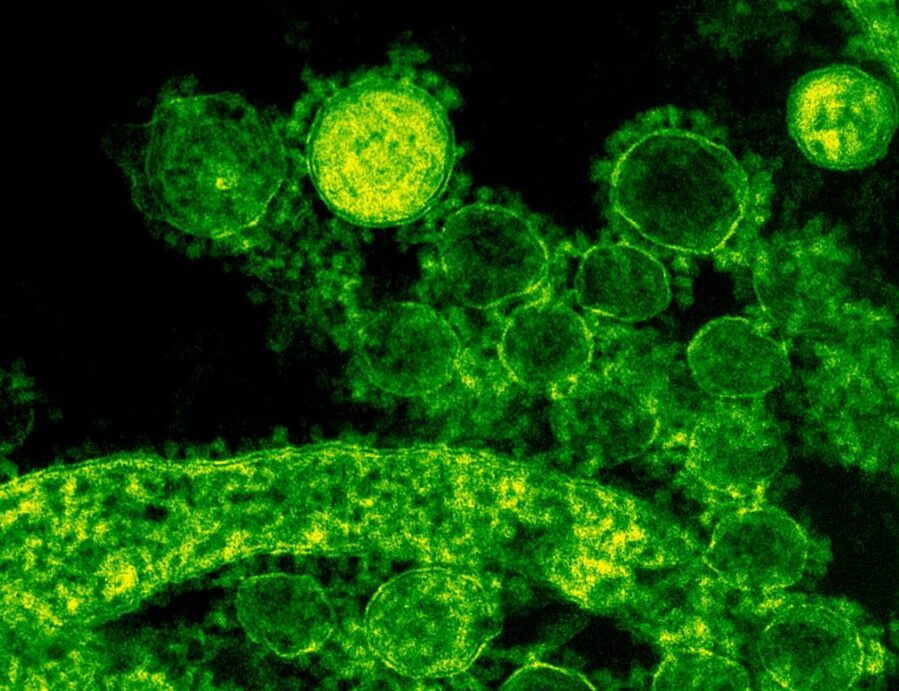

Spacecraft assembly facilities at Kennedy Space Center are scrubbed to near-sterility, blasted with ultraviolet light, and flooded with industrial disinfectants. Yet when researchers sequenced bacteria collected during the Phoenix Mars lander’s assembly, they found something unexpected: 26 entirely new species, thriving precisely because of the extreme conditions meant to eliminate them.

The study, led by Junia Schultz and Kasthuri Venkateswaran and published in Microbiome, analyzed genomes from 215 bacterial isolates. Among them, 53 strains belonged to species never before described. These aren’t common contaminants that slipped through protocols. They’re extremotolerant specialists that have turned NASA’s decontamination gauntlet into an evolutionary advantage.

Metagenomic mapping revealed these novel species account for less than 0.1 percent of total microbial DNA in cleanrooms, making them the rare “dark matter” of these facilities. They persist in a state of prepared dormancy, equipped with molecular tools that allow them to withstand radiation, chemical assault, and months without nutrients. When conditions shift even slightly, a trace of humidity or a stray nutrient molecule, they’re ready.

How Extreme Cleaning Breeds Resilience

The cleanroom environment functions as an evolutionary filter. By removing most competitors, it favors organisms with specialized resistance mechanisms. Genomic analysis showed that spore-forming species and several actinobacterial strains carry resistance-conferring proteins that regulate DNA repair, membrane transport under radiation stress, and transcription control when exposed to disinfectants.

Many species also possess genes for biofilm formation, including BolA and CvpA proteins predominantly found in proteobacterial members, and YqgA regulators detected in most spore-formers. These biofilms act like molecular armor, allowing bacteria to anchor to surfaces and protect themselves from cleaning chemicals. Cell fate regulators controlling sporulation and competence were observed in all spore-forming species, giving them additional survival options when conditions deteriorate.

“The reduced microbial competition in these environments enhances the discovery of novel microbial diversity, contributing to the mitigation of microbial contamination and fostering biotechnological innovation,” Schultz explains.

The findings challenge assumptions about non-spore-forming bacteria, which were previously thought less capable of long-term survival in arid conditions. Several of the newly identified species demonstrate that specialized stress responses can substitute for sporulation, allowing them to persist for years in spacecraft facilities.

Unexpected Biochemical Capabilities

Some discoveries extended beyond survival mechanisms into practical applications. Agrococcus phoenicis, Microbacterium canaveralium, and Microbacterium jpeli all contained biosynthetic gene clusters for epsilon-poly-L-lysine, a natural preservative used in food science and biomedical products. Two novel Sphingomonas species carried genes for zeaxanthin production, an antioxidant essential for human eye health.

Paenibacillus canaveralius harbored genes for bacillibactin, crucial for iron acquisition in nutrient-poor environments. Georgenia phoenicis possessed clusters for alkylresorcinols, compounds with antimicrobial and anticancer properties valuable in pharmaceuticals and food preservation.

For NASA, understanding these resilient residents matters for planetary protection. Future Mars missions and sample return operations require contamination control strategies that account for extremotolerant bacteria capable of surviving spacecraft journeys. The study suggests that even with rigorous protocols, certain organisms may persist through launch, transit, and landing.

But the research also reframes cleanrooms as discovery engines. By filtering out common microbes, these facilities expose rare biology usually hidden in more crowded environments. What began as a contamination risk assessment has revealed microbial diversity with potential applications in medicine, biotechnology, and our understanding of life’s limits. Absolute sterility, it turns out, doesn’t eliminate life. It just reshapes it into forms we’re only beginning to recognize.

Microbiome: 10.1186/s40168-025-02082-1

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!