Micro Implant Listens To A Mouse Brain All Year

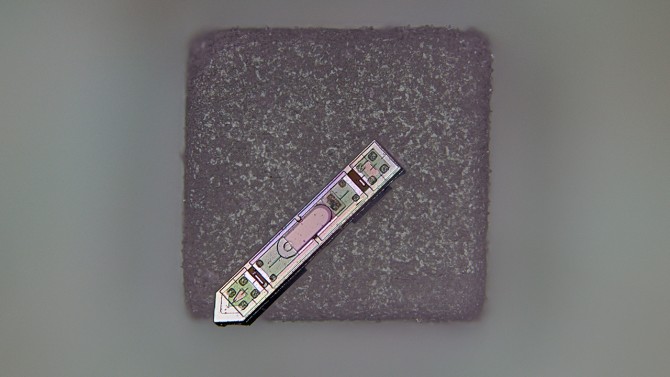

It looks like a speck, no bigger than a fleck of salt, yet it hears the crackle of neurons for months at a time. Cornell engineers and collaborators have built a microscale, wireless neural implant that records brain activity in living mice for more than a year, according to a study published Nov. 3 in Nature Electronics. The device, called a microscale optoelectronic tetherless electrode, or MOTE, pushes neural monitoring into truly subnanoliter territory.

Unlike radio frequency or ultrasound implants that tend to be bottlenecked by the physics of long wavelengths, this system leans on light. Red light powers it. Infrared light sends the data back. There are no wires, no coils, no batteries, only a sliver of semiconductor bonded to CMOS circuitry and wrapped in platinum shielding and atomic layer deposition films to survive the corrosive bath of living tissue.

The scale is startling. A typical MOTE is roughly 300 microns long and 70 microns wide, smaller than a grain of table salt and thinner than a human hair. In the lab description, it is shown balanced beside a hair like a single glittering crumb. That small footprint matters, the team argues, because displaced brain volume and tether motion both drive inflammation and signal drift in conventional setups.

“As far as we know, this is the smallest neural implant that will measure electrical activity in the brain and then report it out wirelessly.”

said senior author Alyosha Molnar in the university announcement. He and co-lead author Sunwoo Lee, now at Nanyang Technological University, report that the MOTE communicates using pulse position modulation, a scheme borrowed from optical satellite links. Short, bright pulses encode information in their timing, not their amplitude, letting the device sip power while still punching through tissue scattering to a photodetector outside the head.

In awake mice with whisker stimulation, the team captured both fast action potentials and slower local field potentials. Recordings persisted across months, with some electrodes still producing decodable signals at day 365. Histology suggested relatively muted microglial responses compared with larger optical fibers, a hint that shrinking the hardware footprint does, in fact, ease the brain’s foreign body reaction.

Light In, Light Out, Signals Intact

The optoelectronic trick hinges on a single aluminum gallium arsenide diode that moonlights as both a photovoltaic collector and a light emitter, time sharing between power intake and data output. A low noise amplifier shapes the neural voltage into a PPM stream, while a charge pump stacks capacitors to drive efficient LED pulses. All of it runs on about a microwatt. It is an unapologetically asymmetric system, where the implant is minimalist and the external optics do the heavy lifting.

There are practical upsides to photons. Red and near infrared wavelengths lose less energy in brain tissue than visible green or blue, reducing heat and allowing deeper placement. The researchers limited incident irradiance far below thermal safety thresholds reported in the literature, and platinum light shields over the CMOS help prevent spurious photo currents that would otherwise swamp such delicate electronics.

The possibility space opens beyond cortex. The authors sketch future versions for organoids, invertebrates, spinal cord, and even scenarios where opto-electronics live beneath a cranial prosthetic. They also note a tantalizing compatibility with MRI. Because the device is not a long conductive wire, it could one day offer electrophysiology during scans that are currently off limits with traditional metal leads. That claim will need testing, but it is an example of how scaling down may scale up experimental options.

What It Will Take To Leave The Lab

The study is an engineering tour de force, but translation will hinge on a familiar checklist. Yield and reproducibility must hold as fabrication scales from dozens to thousands of MOTEs per wafer. Chronic stability at one year is impressive; multi year performance will matter for many applications. Decoding and synchronization pipelines will need to move from benchtop oscilloscopes into robust, real time software. And while the mouse work is compelling, different tissues and motion regimes will stress the design in new ways.

Still, the central claim lands with unusual clarity, straight from the peer reviewed manuscript:

“We show that the subnanolitre neural implant is capable of chronic (365 days) in vivo recordings in awake mice.”

That is a sentence worth pausing on. For years, the field has chased tetherless implants tiny enough to dodge biology’s defensive reflexes without surrendering bandwidth or longevity. This study offers a convincing demonstration that light powered, light reporting chips, smaller than a salt grain, can listen to living brains for a very long time. The next test is whether they can do it widely, cheaply, and in places the old hardware could never reach.

Nature Electronics: 10.1038/s41928-025-01484-1

If our reporting has informed or inspired you, please consider making a donation. Every contribution, no matter the size, empowers us to continue delivering accurate, engaging, and trustworthy science and medical news. Independent journalism requires time, effort, and resources—your support ensures we can keep uncovering the stories that matter most to you.

Join us in making knowledge accessible and impactful. Thank you for standing with us!